In a previous post of this blog, I mentioned about getting into explorations into Erlang. As with beginning to learn any new thing, it is always good if we could beforehand know of what are the domains in which it is strong, and what are the benefits it could offer in those areas. To examine one of the use cases for it, let's consider this common scenario.

As any public site or web service increases in popularity, it follows that the number of concurrent users at any moment of time correspondingly increases.1

Typical operations such as requesting a webpage, creation of new user accounts, or querying for data keep incessantly coming in at a fast and furious rate.

A web service which is not capable of handling a large amount of concurrent incoming requests will either respond extremely slowly to each request, or many requests may just fail outright. This is especially exacerbated in operations that do not quickly complete - for example, if the operation needs the server to itself make an outgoing request to yet another remote backend. Having the quality of service adversely afflicted by this kind of 'paralysis' seems even more unacceptable, especially when you note that during the bombardment of incoming requests, the server's CPU utilization is actually extremely low. In effect, our server is actually spending most of its time doing nothing but waiting - yet is unable to accept and service more incoming requests.

To find out the capabilities of our server, we carry out load testing on it. Of which, the methodology is more or less succinctly summarized by this comic strip.

The problem of handling many simultaneous clients is dubbed the C10K problem, and there are several approaches to tackle it. To name some of them:

- scaling (adding more servers),

- changing specific software libraries, or

- changing the underlying technology and programming paradigm.

A recent query about the throughput of a webservice I was involved in writing necessitated load testing on our API and sparked off a comparison between a Python-implemented service (behind nginx webserver) and an Erlang-implemented one (no separate webserver running; just using the Cowboy webserver library, which is pure Erlang code.)

To summarize, we found that the Python service's

- throughput hit a ceiling of 18 requests/s from 32 concurrent users

- increasing to 64 concurrent users does not increase the req/s - however the average response time becomes twice as long

- increasing even further to 256 concurrent users gets a lot (30%-50%) of error responses, specifically 502 Bad Gateway or outright "connection refused"

In contrast, running on the same hardware configuration,

- The Erlang service performed with 0% error responses even with 512 concurrent users (higher concurrent user count was not tested)

- The response time is as long as the external remote backend's response time, with very little overhead from our Erlang service (for our tests, we requested the main page of very popular search engine)

- Our Erlang service, in the same request, also wrote and queried a MySQL database and to an in-memory cache, performing the equivalent of all the operations of the Python service

- The throughput for this was 121 req/s

- It was able to accept incoming requests and send out outgoing requests at the same rate

- When the outgoing request was replaced with a simulation of an extremely slow backend by using an 8-second sleep, the throughput for 512 concurrent users was still a commendable rate of 60/s

- Without any remote call or sleep, 256 concurrent users can achieve a throughput of 316/s

- Hot-code reloading i.e. changing the logic on-the-fly without disconnecting ongoing requests or having to restart the server, yet automatically switching new requests to the new logic was also demonstrated (this is a side exploration done while the server was under load; not as a performance-influencing attempt.)

In addition, the Python service consumed more memory when the number of its 'workers' was increased in an attempt to stretch its capability. The Erlang service was observed to consume practically an almost constant amount of memory throughout its operation. CPU utilization during the bombardment of requests was constantly low, which is consistent with our operation not being a CPU-bound workload.

In the preceding section, we have summarized the server characteristics under load.

So we would like to attempt an explanation, about why is there such a difference in the load-handling capability, when the hardware never changed.

When an incoming request hits a typical Python webapp, a 'worker' handles the request from its initiation until the response is formed and returned to the client. There are a few models of what this 'worker' is, in default configurations it is usually an OS thread, either one-to-one for workers to threads, or possibly in some other configuration.

When all requests complete quickly, the number of incoming requests queued will be able to be serviced by the finite pool of workers. Therefore we will not be noticing any problem. The problem comes when the operation is slow, as in the case of the server itself making remote requests. When all the workers are busy waiting for a response, during that time, no incoming request is able to be accepted nor serviced. Consequently, the rate of outgoing requests made is constrained by all the outgoing requests currently taking up all the workers at that time.

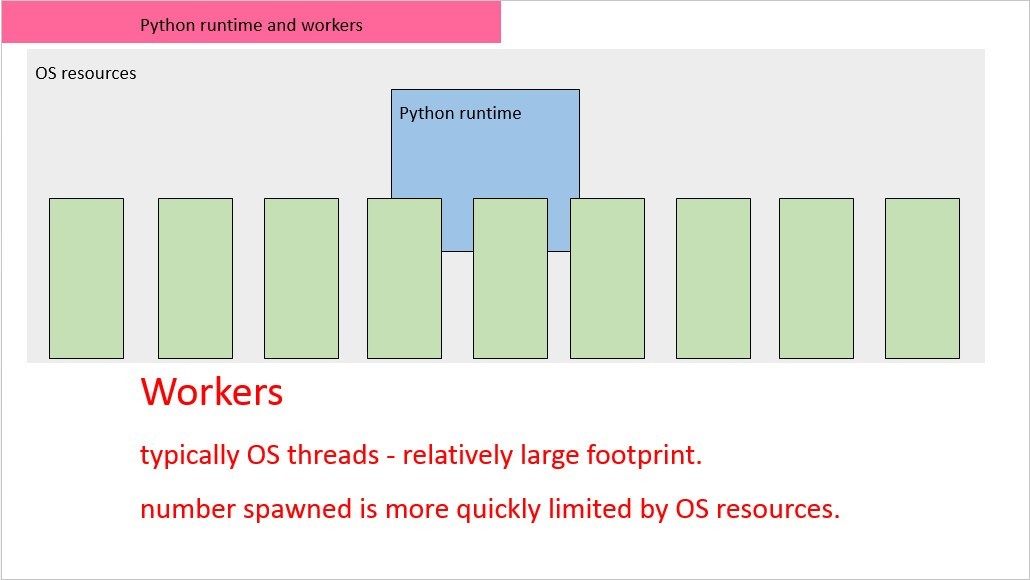

The following diagram shows, conceptually, workers in a Python webapp. The workers which are typically OS threads each take up a considerable footprint of OS resources, particularly memory. This limits the extent to which one can scale by increasing the number of workers.

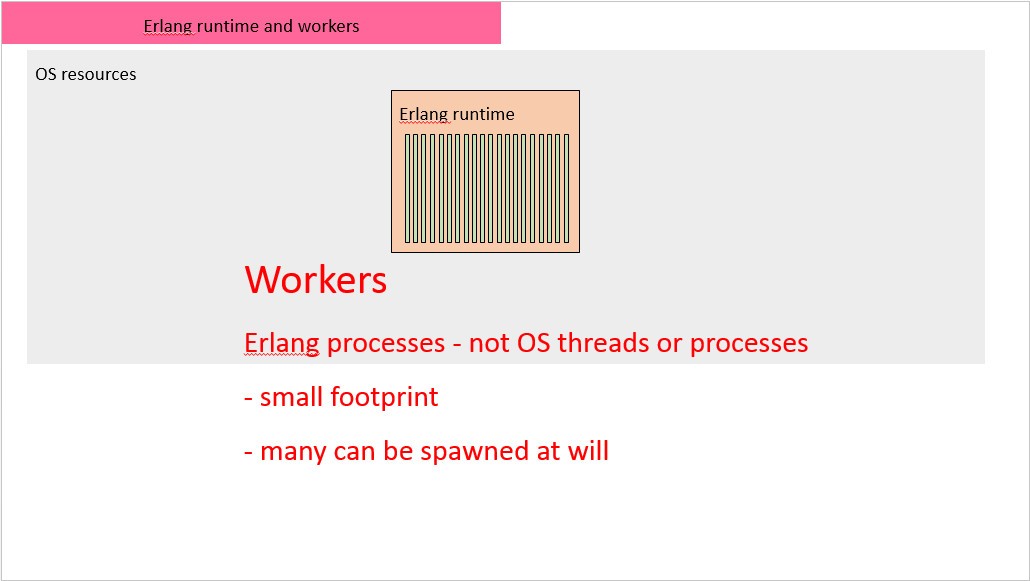

In an Erlang app, the workers are actually constructs within the Erlang runtime called 'processes', of which each one takes up an extremely small amount of memory. It is not uncommon for 100,000 such workers to be able to be spawned within an Erlang process.

Behaviourally, workers in Erlang behave similarly as OS processes, but without the footprint and overhead of actual OS processes (or threads.) Which is why they are named 'processes'. This is illustrated in the following diagram:

This makes Erlang ideal for the use case of handling a large amount of IO-bound operations, that is, operations that spend most of the time waiting rather than actively processing. In our use case, an incoming request is each accepted and handled by its own individual Erlang process, which performs the db tasks, sends the outgoing request, and waits for the response. During this time, new incoming requests are still able to be readily accepted and handled, because it is so cheap to spawn Erlang processes.

We also note that the requests to our Python webapp are routed through the nginx webserver in front, as is typically configured. In the case of Erlang, the Cowboy Erlang webserver, entirely implemented in Erlang code, and the Erlang runtime itself are all that is needed to provide the same functionality, at the same time without requiring an inordinately large amount of RAM.

Closing words

So, what did we learn from all this? Firstly, we identified one of the use cases where Erlang shines, and this gives us at least one compelling reason to find out more about this seemingly less-hyped, but surprisingly effective option. Next, is it worth the effort to tackle the strange syntax, programming paradigms and unfamiliar (yet effective) toolchain that using Erlang requires?

In my opinion, the answer is 'Yes', and I look at it this way:

For some applications, they have to be developed in such a low-level language as Assembly Language. The reason being in order to get the specific benefits - e.g. more deterministic execution, faster response, less overhead, etc. - that taking such a deliberate effort confers.

By the same token, for some applications, to get specific characteristic or benefits, they happen to be readily achievable by using the Erlang runtime.

So, the takeaway - just as how one gains specific benefits by programming using Assembly Language targeting a certain embedded processor, we are targeting the Erlang runtime to achieve the specific benefits therefrom, so we use Erlang language2 to program for that runtime.

Thanks for reading! Let me know if you found any inaccuracies, or would like to add to the discussion or if there are any questions.

With this in mind, we have a compelling reason to begin learning Erlang.

In future installments, we will explore more about how to start making Erlang work for us.

-

Though the revelatory degree of this statement can be summed up thus: Who doesn't know his mom is a woman? ↩

-

The useful properties of the Erlang runtime has been recognized by some and gained some traction, thus languages such as Lisp-Flavored Erlang (LFE) and the Ruby-esque Elixir have surfaced, of which you write your code in those languages, and they target the Erlang runtime all the same. ↩